di

L’immaginazione dell’artista di un gruppo di eucarioti primitivi del “Protosterol Biota” che vivono su un tappeto batterico sul fondo dell’oceano. Sulla base di fossili molecolari, gli organismi Protosterol Biota hanno vissuto negli oceani da circa 1,6 a 1,0 miliardi di anni fa e sono i nostri più antichi antenati conosciuti. Credito: organizzato su MidJourney da TA 2023

Un gruppo di ricerca multinazionale ha trovato antichi protosteroidi nelle rocce, indicando che la vita complessa esisteva già 1,6 miliardi di anni fa. Queste molecole forniscono nuove informazioni sull’evoluzione della vita complessa e riconciliano le discrepanze tra i reperti fossili tradizionali e quelli lipidici.

Si scopre che il record appena scoperto dei cosiddetti protosteroidi era sorprendentemente abbondante per tutto il Medioevo della Terra. Le molecole primordiali sono state prodotte in una fase iniziale nella complessità degli eucarioti, estendendo l’attuale record di steroli fossili oltre 800 e persino 1.600 milioni di anni fa. Eucarioti è un termine dato al regno della vita che include tutti gli animali, le piante e le alghe ed è separato dai batteri avendo una struttura cellulare complessa che include un nucleo, nonché un meccanismo molecolare più complesso.

“Il momento clou di questa scoperta non è semplicemente un’estensione dell’attuale documentazione molecolare degli eucarioti”, afferma Christian Hollmann, uno dei co-scienziati del Centro di ricerca tedesco per le geoscienze (GFZ) di Potsdam. “Dato che l’ultimo antenato comune di tutti gli eucarioti moderni, inclusi noi umani, era probabilmente in grado di produrre steroli moderni” regolari “, è probabile che gli eucarioti responsabili di queste rare firme appartengano al tronco dell’albero filogenetico”.

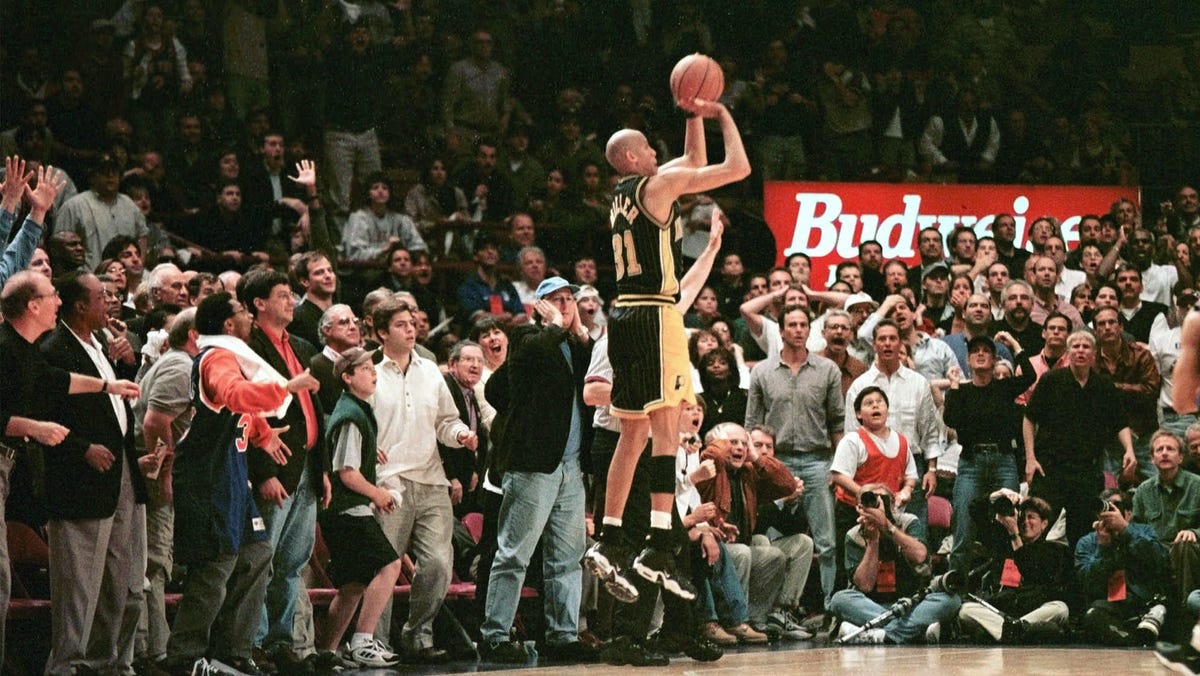

Benjamin Nettersheim, uno degli autori principali dello studio, esamina le mappe elementali e molecolari a super-risoluzione di campioni di roccia di 1,64 miliardi di anni analizzati nel Geobiological Molecular Imaging Laboratory del MARUM. Crediti: MARUM – Centro di Ecologia Marina, Università di Brema; in Descamps

Questo “ceppo” rappresenta il comune lignaggio ancestrale che fu il precursore di tutti i rami viventi degli eucarioti. I suoi rappresentanti sono estinti da tempo, ma i dettagli della loro natura possono gettare più luce sulle circostanze che circondano l’evoluzione della vita complessa. Sebbene siano necessarie ulteriori ricerche per valutare quale percentuale di protosteroidi possa avere una rara fonte batterica, la scoperta di queste nuove molecole non solo riconcilia la documentazione geologica dei fossili tradizionali con quella delle molecole di grasso fossile, ma offre uno sguardo raro e senza precedenti nel mondo perso dalla vecchia vita. La scomparsa competitiva degli eucarioti del gruppo staminale, segnata dalla prima apparizione dei moderni fossili stromali circa 800 milioni di anni fa, potrebbe riflettere uno degli eventi più duraturi nell’evoluzione di una vita sempre più complessa.

aggiunge Benjamin Nittersheim di Marom, Università di Brema, che è stato co-autore dello studio insieme a Jochen Brooks di[{” attribute=””>Australian National University (ANU) – “due to potentially adverse health effects of elevated cholesterol levels in humans, cholesterol doesn’t have the best reputation from a medical perspective. However, these lipid molecules are integral parts of eukaryotic cell membranes where they aid in a variety of physiological functions. By searching for fossilized steroids in ancient rocks, we can trace the evolution of increasingly complex life.”

Dr. Nettersheim inserts a thin section and rock slices of 1.64 billion-years old rocks into the 7T solariX XR FT-ICR-MS equipped with a MALDI source at the Geobiomolecular Imaging Laboratory at MARUM. As part of ongoing research into mid-Proterozoic biomarker signatures at MARUM, GFZ and the Australian National University, Dr. Nettersheim aims to zoom into the cradle of eukaryotic life in unprecedented resolution. Credit: MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen; V. Diekamp

Nobel laureate Konrad Bloch had already speculated about such a biomarker in an essay almost 30 years ago. Bloch suggested that short-lived intermediates in the modern biosynthesis of steroids may not always have been intermediates. He believed that lipid biosynthesis evolved in parallel with changing environmental conditions throughout Earth history. In contrast to Bloch, who did not believe that these ancient intermediates could ever be found, Nettersheim started searching for protosteroids in ancient rocks that were deposited at a time when those intermediates could actually have been the final product.

But how to find such molecules in ancient rocks? “We employed a combination of techniques to first convert various modern steroids to their fossilized equivalent; otherwise, we wouldn’t have even known what to look for,” says Jochen Brocks. Scientists had overlooked these molecules for decades because they do not conform to typical molecular search images. “Once we knew our target, we discovered that dozens of other rocks, taken from billion-year-old waterways across the world, were oozing with similar fossil molecules.”

The oldest samples with the biomarker are from the Barney Creek Formation in Australia and are 1.64 billion years old. The rock record of the next 800 million years only yields fossil molecules of primordial eukaryotes before molecular signatures of modern eukaryotes first appear in the Tonian period. According to Nettersheim “the Tonian Transformation emerges as one of the most profound ecological turning points in our planet´s history“. Hallmann adds that “both primordial stem groups and modern eukaryotic representatives such as red algae may have lived side by side for many hundreds of millions of years”. During this time, however, the Earth’s atmosphere became increasingly enriched with oxygen – a metabolic product of cyanobacteria and of the first eukaryotic algae – that would have been toxic to many other organisms. Later, global “Snowball Earth” glaciations occurred and the protosterol communities largely died out. The last common ancestor of all living eukaryotes may have lived 1.2 to 1.8 billion years ago. Its descendants were likely better able to survive heat and cold as well as UV radiation and displaced their primordial relatives.

“Earth was a microbial world for much of its history and left few traces,” Nettersheim concludes. Research at ANU, MARUM and GFZ continues to pursue tracing the roots of our existence – the discovery of protosterols now brings us one step closer to understanding how our earliest ancestors lived and evolved. Shooting at the ancient rocks with a laser coupled to an ultra-high resolution mass spectrometer in MARUM’s globally unique Geobiomolecular Imaging Laboratory, Dr. Nettersheim and his international collaborators aim at zooming into the cradle of eukaryotic life in unprecedented resolution to further improve our understanding of our early ancestors in the future.

Reference: “Lost world of complex life and the late rise of the eukaryotic crown” by Jochen J. Brocks, Benjamin J. Nettersheim, Pierre Adam, Philippe Schaeffer, Amber J. M. Jarrett, Nur Güneli, Tharika Liyanage, Lennart M. van Maldegem, Christian Hallmann and Janet M. Hope, 7 June 2023, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06170-w

Participating Institutions:

- Research School of Earth Sciences, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

- MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

- Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

- Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, Institut de Chimie de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France

- Northern Territory Geological Survey, Darwin, Australia

- German Research Center for Geosciences (GFZ), Potsdam, Germany

MARUM produces fundamental scientific knowledge about the role of the ocean and the ocean floor in the total Earth system. The dynamics of the ocean and the ocean floor significantly impact the entire Earth system through the interaction of geological, physical, biological and chemical processes. These influence both the climate and the global carbon cycle, and create unique biological systems. MARUM is committed to fundamental and unbiased research in the interests of society and the marine environment, and in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations. It publishes its quality-assured scientific data and makes it publicly available. MARUM informs the public about new discoveries in the marine environment and provides practical knowledge through its dialogue with society. MARUM cooperates with commercial and industrial partners in accordance with its goal of protecting the marine environment.

“Devoto esploratore. Pluripremiato sostenitore del cibo. Esasperante umile fanatico della tv. Impenitente specialista dei social media.”

More Stories

Gli astronomi risolvono il mistero della drammatica esplosione del 1936 di FU Orionis

Un razzo SpaceX Falcon 9 lancia due satelliti durante il ventesimo volo record

Giovedì sera, SpaceX punta al lancio nel 2024 del suo 33esimo razzo Cape